Shih-Hua Fanga, Yerra Koteswara Raob, and Yew-Min Tzengb* a Department of Microbiology, School of Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung 400, Taiwan, R.O.C.

b Institute of Biotechnology, Chaoyang University of Technology, Wufeng, Taichung country 413, Taiwan, R.O.C.

Download Citation:

|

Download PDF

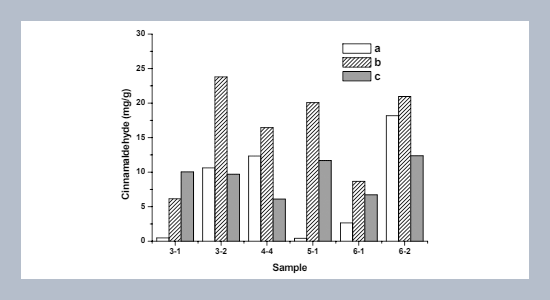

Quantitative determination of trans-cinnamaldehyde (TCA) was conducted by reversed-phase HPLC from young and mature leaves, and leaf branches of Cinnamomum osmophloeum, a Taiwan endemic plant. The results showed that highest yield, 23.79 mg/g of TCA (the tree’s age was three years) was obtained in the two year old mature leaves. In addition, cytotoxic and inhibitory effects of TCA was evaluated against selected human cancer cell lines such as Jurkat, U937, and normal cell lines primary purified T cells and macrophages. The results revealed that TCA exhibited potent inhibitory activity against Jurkat and U937 cell viability, and found that the IC50 values were 0.057, 0.076 μM, respectively. In parallel, no effect on the viability of primary purified T cells and macrophages. Moreover, interestingly at 0.095 μM, TCA inhibited proliferation of both Jurkat and U937 cell lines approximately 2-fold at 0.057 μM, compared to controls. In contrast, TCA increases approximately 26% proliferation of mitogen-stimulated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) during the concentration range studied. Furthermore, by cell cycle analysis, we found that TCA altered the cell cycle phase distribution of Jurkat and U937 cells in a nonlinear concentration-dependent fashion. Taken together our results suggest that TCA may be a useful chemotherapeutic agent for cancer treatment in human.ABSTRACT

Keywords:

Cinnamomum osmophloeum; trans-cinnamaldehyde; cytotoxic; Jurkat cell; U937 cell; PBMCs.

Share this article with your colleagues

[1] Morse, M. A. and Stoner, G. D. 1993. Cancer chemoprevention: principles and prospects. Carcinogenesis, 14: 1737-1746.REFERENCES

[2] Mclarty, J. W. 1997. Antioxidants and cancer: the epidemiologic evidence. In: Garewal, H.S. (Ed.). “Antioxidants and Disease Prevention”. CRC Press, New York: 45-66.

[3] Abdulla, M. and Gruber, P. 2000. Role of diet modification in cancer prevention. Biofactors, 12, 1-4: 45-51.

[4] Kromhout, D. 2001. Diet and cardiovascular diseases. Journal of Nutrition and Health Aging, 5, 3: 144-149.

[5] Sun, J., Chu, Y. F., Wu, X. Z., and Liu, R. H. 2002. Antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of common fruits. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 50, 25: 7449-7454.

[6] Lien, E. J. and Li, W. Y. 1985. Structure-activity relationship analysis of chinese anticancer drugs and related plants. Oriental Healing Arts Institute, Long Beach, CA, S.A.

[7] Tsai, T. H. 2001. Analytical approaches for traditional Chinese medicines exhibiting antineoplastic activity. Journal of Chromatography B, 764, 1-2: 27-48.

[8] Hu, T. W., Lin, Y. T., and Ho, C. K., 1985. Natural variation of chemical components of the leaf oil of Cinnamomum osmophloeum Bulletin of Taiwan Forest Research Institute, 78: 18-25.

[9] Hussain, R. A., Kim, J., Hu, T. W., Pezzuto, J. M., Soejarto, D. D., and Kinghorn, A. D. 1986. Isolation of a highly sweet constituent from Cinnamomum osmophloeum Planta Medica, 5: 403-404.

[10] Lee, H. S. and Ahn, Y. J. 1998. Growth-inhibiting effects of Cinnamomum cassia bark-derived materials on human intestinal bacteria. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 46, 1: 8-12.

[11] Chang, S. T., Chen, P. F., and Chang, S. C. 2001. Antibacterial activity of leaf essential oils and their constituents from Cinnamomum osmophloeum. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 77, 1: 123-127.

[12] Chang, S. T. and Chen, S. S. 2002. Antitermitic activity of leaf essential oils and components from Cinnamomum osmophleum. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 50, 6: 1389-1392.

[13] Koh, W. S., Yoon, S. Y., Kwon, B. M., Jeong, T. C., Nam, K. S., and Han, M. Y. 1998. Cinnamaldehyde inhibits lymphocyte proliferation and modulates T-cell differentiation. International Journal of Immunopharmacology, 20, 11: 643-660.

[14] Kwon, B. M., Lee, S. H., Choi, S. U., Park, S. H., Lee, C. O., and Cho, Y. K. 1998. Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity of cinnamaldehydes to human solid tumor cells. Archives of Pharmacology Research, 21: 147-152.

[15] Shaughnessy, D. T., Setzer, R. W., and DeMarini, D. M. 2001. The antimutagenic effect of vanillin and cinnamaldehyde on spontaneous mutation at GC but not AT sites. Mutation Research, 480-481: 55-69.

[17] Klibanov, A. M. and Giannousis, P. P. 1982. Geometric specificity of alcohol dehydrogenases and its potential for separation of trans and cis isomers of unsaturated aldehydes. Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences U.S.A, 79, 11: 3462-3465.

[18] Van, I. M. L., Ploemen, J. P., Lo, B. M., Federici, G., and Van, B. P. J. 1997. Interactions of alpha, beta-unsaturated aldehydes and ketones with human glutathione S-transferase P1-1. Chemistry Biology Interact, 108, 1-2: 67-78.

[19] Lee, H. S. 2002. Tyrosinase inhibitors of Pulsatilla cernua root-derived materials. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 50, 6: 1400-1403.

[20] Usta, J., Kreydiyyeh, S., Barnabe, P., Bou, M. Y., and Nakkash, C. H. 2003. Comparative study on the effect of cinnamon and clove extracts and their main components on different types of ATPases. Human Experimental Toxicology, 22, 7: 355-362.

[21] Jeong, H. W., Kim, M. R., Son, K. H., Han, M. Y., Ha, J. H., Garnier, M., Meijer, L., and Kwon, B. M. 2000. Cinnamaldehydes inhibit cyclin dependent kinase 4/cyclin D1. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 10: 1819-1822.

[22] Lee, S. H. 2002. Inhibitory activity of Cinnamomum cassia bark-derived component against rat lens aldose reductase. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 5, 3: 226-230.

[23] Fang, S. H., Chiang, B. L., Wu, M. H., Iba, H., Lai, M. Y., Yang, P. M., Chen, D. S., and Hwang, L. H. 2001. Functional measurement of Hepatitis C virus core-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in the livers or peripheral blood of patients by using autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells as targets or stimulators. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 39, 11: 3895-3901.

[24] Suen, J. L., Chuang, Y. H., and Chiang, B. L. 2002. In vivo tolerance breakdown with dendritic cells pulsed with U1A protein in non-autoimmune mice: the induction of a high level of autoantibodies but not renal pathological changes. Immunology, 106, 3: 326-335.

[25] Tian, Q., Miller, E. G., Ahmad, H., Tang., L., and Patil, B. S. 2001. Differential inhibition of human cancer cell proliferation by citrus limonoids. Nutritional Cancer, 40, 2: 180-184.

[26] Fang, S. H., Lai, M. Y., Hwang, L. H., Yang, P. M., Chen, P. J., Chiang, B. L., and Chen, D. S. 2001. Ribavirin enhances interferon-γ levels in patients with chronic Hepatitis C treated with interferon-α. Journal of Biomedical Science, 8, 6: 484-491.

[27] Miller, A. B. 1991. Role of early diagnosis and screening; biomarkers. Cancer Detection and Prevention, 15, 1: 21-26.

[28] Ka, H., Park, H. J., Jung, H. J., Choi, J. W., Cho, K. S., Ha, J., and Lee, K. T. 2003. Cinnamaldehyde induces apoptosis by ROS-mediated mitochondrial permeability transition in human leukemia HL-60 cells. Cancer Letters, 196, 2: 143-152.

[29] Carnesecchi, S., Schneider, Y., Ceraline, J., Duranton, B., Gosse, F., Seiler, N., and Raul, F. 2001. Geraniol, a component of plant essential oils, inhibits growth and polyamine biosynthesis in human colon cancer cells. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 298, 1: 197-200.

[30] Tatman, D. and Mo, H. 2002. Volatile isoprenoid constituents of fruits, vegetables and herbs cumulatively suppress the proliferation of murine B16 melanoma and human HL-60 leukemia cells. Cancer Letters, 175, 2: 129-139.

[31] Fussenegger, M. and Bailey, J. E. 1998. Molecular regulation of cell-cycle progression and apoptosis in mammalian cells: implications for biotechnology. Biotechnology Progress, 14, 6: 807-833.

[32] Carlson, B., Lahusen, T., Singh, S., Loaiza, P. A., Worland, P. J., Pestell, R., Albanese, C., Sausville, E. A., and Senderowicz, A. M. 1999. Down-regulation of cyclin D1 by transcriptional repression in MCF-7 human breast carcinoma cells induced by flavopiridol. Cancer Research, 59, 18: 4634-4641.

[33] Xiao, K. L., Monica, M., William, T., William, B., and Gary, K. S. 2000. Huanglian, a Chinese herbel extract, inhibits cell growth by suppressing the expression of cyclin B1 and inhibiting CDC2 kinase activity in Human Cancer Cells. Molecular Pharmacology, 58, 6: 1287-1293.

[34] Jeong, H. W., Han, D. C., Son, K. H., Han, M. Y., Lim, J. S., Ha, J. H., Lee, C. W., Kim, H. M., Kim, H. C., and Kwon, B. M. 2003. Antitumor effect of the cinnamaldehyde derivative CB403 through the arrest of cell cycle progression in the G2/M phase. Biochemical Pharmacology, 65, 8: 1343-1350.

[35] Elledge, S. J. 1996. cell cycle checkpoints: preventing and identity crisis. Science, 274: 1664-1672.

[36] Grana, X. and Reddy, E. P. 1995. Cell cycle control in mammalian cells: role of cyclins, cyclin dependent kinases (CDKs), growth suppressor genes and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs). Oncogene, 11, 2: 211-219.

[37] Nurse, P. 1990. Universal control mechanism regulating onset of M-phase. Nature, 344, 6266: 503-508.

Sherr, C. J. 1996. Cancer cell cycles. Science, 274: 1672-1677.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

Accepted:

2004-06-16

Available Online:

2004-07-01

Fang, S.-H., Rao, Y.-K., Tzeng, Y.-M. 2004. Cytotoxic effect of trans-Cinnamaldehyde from cinnamomum osmophloeum leaves on human cancer cell lines, International Journal of Applied Science and Engineering, 2, 136–147. https://doi.org/10.6703/IJASE.2004.2.(2).136

Cite this article: